“The Scariest Parts are the True Parts”

Sydney Warner Brooman on their debut short story collection, The Pump

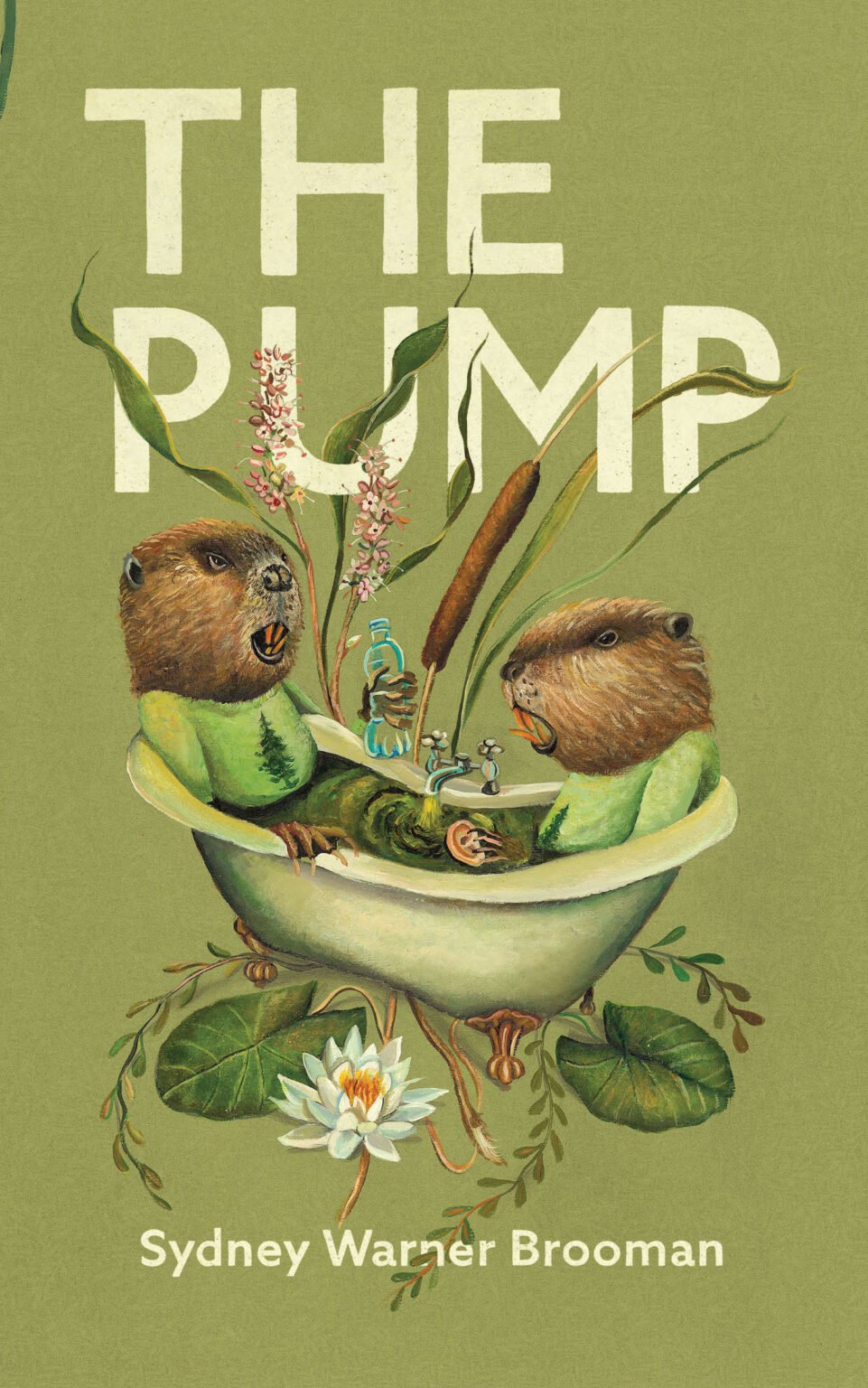

The Pump (Invisible Publishing, 2021).

With The Pump, Sydney Warner Brooman has given readers a debut collection of interconnected short stories that paints a portrait of small town Ontario not seen on the tourism brochures and the CBC. The picturesque main streets with Victorian architecture, clock towers, and planters hanging from street lamps splashed with sun don’t exist in The Pump. That’s the other side, the idyllic small town we feel city-dwellers can flee to. The Pump is what you flee from. We spoke to Brooman about their collection and the fantasies and nightmares of small-town life, the process which created it, and the impact it has had on their life.

The Pump is a collection of interconnected stories set in a small Ontario town. We tend to romanticize small town life, yet, conversely, small towns, though idyllic, are fertile ground for pastoral gothic tales like those in The Pump. What is it about the fantasy of small town life that is so appealing, and why is that so easy to twist into something darker?

The grass is always greener, you know? Wherever there are humans, there are the things that we see, and the dark underbelly that we don’t see. I romanticized cities until I lived in one, so it’s easy for me to see how those who haven’t grown up in a small town could look at the close-knit nature of “knowing one’s neighbour”, and the quiet, quaint nature and think that existence there is somehow better. You don’t see the detrimental effect of everyone in a small population knowing who you are and gossiping about everything you or your family has ever done until you live it. If you are bullied by a classmate in kindergarten, you quite literally grow up with that person through every grade. If you are assaulted by someone in your community, you see them every day. The scariest parts of The Pump are the true parts.

“I think a lot about what it means for the landscape to take its power back, to tell us that we had our chance to take care of it and we failed and now it is time for us to reap what we sowed.”

Like many writers, you work a day job unrelated to writing. Have your coworkers been treating you differently since the release of your book and the buzz it has generated?

I mean, a little? I’ve found that since my career as a writer has accelerated in a short amount of time, or it at least looks like it has, I’ve admittedly become a little desensitized to how cool all of it is. When you’re in spaces with other writers, there is this odd sort of “always focusing on the next thing” attitude that happens. Your daily life is normalized because a lot of the people around you are doing the same things. And then something will happen where I will tell a co-worker that I’m doing a reading for a festival, and they’ll be flabbergasted, and it will take me a moment to be like “Oh yeah, that is really cool.” Maybe a bit of it is imposter syndrome, where I don’t quite believe that I’m a real writer, whatever that means.

Where did you write The Pump? Were you in your hometown of Grimsby, or did another location inspire the stories in this collection?

I wrote all of The Pump in London, Ontario, where I was attending University. The book was my undergraduate thesis project. The majority of the book is inspired by my experiences in Grimsby, processing them after moving away for the first time in my life, but the beavers are definitely a London thing!

How much does the place we live in impact who we are? Is our hometown in our DNA?

I think, at first, it is everything. And then, it is whatever we make of it. I am certainly shaped by my childhood in Grimsby, but the place I grew up in is not all that I am. I am other things. Other places. Other experiences. Other people. I do think our hometown is in our DNA, but DNA is not the only way we move through the world.

There’s a very horror-movie feel to many of these stories, and like many horror stories, the terror comes from characters ignoring a natural harmony. Would it be fair to say that The Pump is a critique of the industrial disregard for the environment?

I think that would be fair, yes. A lot of my positive childhood experiences came from exploring the landscape of the Niagara Escarpment, the Bruce trail, Lake Ontario. As I grew older, the lake became too contaminated to swim in, and stop freezing over in the winter. I think a lot about what it means for the landscape to take its power back, to tell us that we had our chance to take care of it and we failed and now it is time for us to reap what we sowed.

Familiar animals, symbols of birth, Canada and industriousness symbolize menace in The Pump. What prompted you to flip the script on symbols that historically bring us comfort?

Some people find comfort in these things, but a lot of others don’t. I don’t think I so much flipped the script as I just made a few missing pages readable.

Is writing a compulsion for you, like it is for Eloise in your story “Vellum”?

It definitely was when I was young—when my writing had nothing to do with making money or winning awards. I have a healthier relationship with it now. Eloise’s writing sickness has a lot to do with our relationships to our bodies as well. Back when I wrote that story, I was suffering in that area. I’d like to think I’m healthier in that way now, too.

The looming fatality of small town life haunts these stories. Do you think there is an equivalent sense in stories set in a major urban centre, or is it the lack of anonymity that makes life seem so finite

Sometimes I think that small town people long to be forgotten, and city people long to be remembered, and neither of the get what they want unless they move away, but when they do, they end up wanting the opposite.

A sense of powerlessness pervades the stories in your collection, as though these characters are stuck in ruts that accepted as their fate. Is there a way out for these characters or are they a latter day Sisyphus, cursed to stay in their ruts for the rest of their lives?

When I began writing The Pump, I thought that small town people, particularly queer people, only had two options in their lives: they could change—try to be like everyone else— or they could leave. I left. Now, after writing the book, I realize that I’m really seeking a third option. A way in which a queer person stays in their town to make space for others like them. A reality where the people change the town, and not the other way around. I long for a story like that. I long for a future like that.